The Nature of Our Power: A Conversation with Political Scientist Erica Chenoweth

"The best study on the subject in my opinion suggests that in the long term, institutions really can’t save us; that civil society and mass mobilization are a more potent check on a backsliding democracy in the long term than relying on institutional checks and balances alone." That's what political scientist Erica Chenoweth told me when I asked them if we could have a conversation (by email, below in full) about the current constitutional crisis/coup attempt and what we can do about it. Chenoweth is a hugely influential scholar of nonviolent social change, best known for their empirical research that not only documents what makes civil resistance work but demonstrates that it works, often extremely effectively. They direct the Nonviolent Action Lab, which studies how people have built movements and developed strategies to resist authoritarianism successfully and documents how nonviolence can be effective. There's no one I wanted to hear from more in this constitutional crisis, and I'm grateful I can share their insights with all of you.

Rebecca: When you look at what Musk and Trump are doing that is illegal because it’s beyond the powers granted to the administrative branch, and damaging longstanding institutions and relationships, what does that tell you about their understanding—or lack of understanding—of these systems and entities and the nature of power?

Erica: It tells me that they believe—and fear—that they cannot implement their policies and plans without the cooperation, obedience, and help of people in various pillars of support. This is a key insight about the nature of power repeated by Hannah Arendt, Gene Sharp, George Lakey, and others, and which underpins many theories of nonviolent action and civil resistance. Indeed, what Trump and Musk seem to have learned during the first Trump administration is this: subverting institutional checks and balances, subordinating key agencies, ignoring Congress’s law-making authority, dominating the media and information environment, and eliminating oversight and accountability—in other words, pulling off a power grab—is required to achieve their agenda. When you see what autocratic leaders try to eliminate, you get clearer on what constrains or threatens them—and why these systems, procedures, institutions, and the dedicated civil servants within them are so important to protect.

Rebecca: What powers do you see to oppose and shut down this coup attempt, in the legislative and judicial branch of the federal government, states, but especially in civil society? What do you hope to see civil society do in response? Are there particular tactics of civil resistance that seem useful or relevant in this moment?

Erica: Among the most urgent work in a moment of potential backsliding is to both protect the most vulnerable people from direct harm, while also upholding the rule of law. If you don’t defend the rule of law, you lose it, and the terrain becomes much more uncertain and treacherous. Most urgently, this means filing suit against every move that appears to be illegal and/or unconstitutional. We are seeing some of this happening already with regard to the executive orders and some of the firings of inspectors general, etc., but many more such cases would be needed for the federal courts to fully exercise their authority to contain executive power.

Despite a conservative Supreme Court, my bet is that the courts will still be more reliable checks on executive power than Congress in this moment. Trump doesn’t seem to care if his executive orders are ultimately ruled illegal or not, likely expects the court challenges, and likely expects to win some and lose a lot. But we should certainly care about what the courts say, because complying without court rulings otherwise de facto expands his power.

More generally, I hope to see deeper cooperation and coordination in civil society than we have achieved before, to develop an effective power-building strategy to meet the current challenge. There are of course numerous organizing tools and civil resistance tactics that might be relevant to such a strategy, but ideally the strategy would inform the sequence of tactics (and not the other way around). And when it comes to protecting people, your own work has shown all of the creative ways that people figure out how to provide for and care for the most vulnerable during a crisis, including a political emergency.

Rebecca: What are the precedents you think of and what do they tell us about our possibilities and powers in this crisis? Are there coups and crises in other times and places to look to to understand how to respond to the one we have going on here and now?

Erica: The deconsolidation of American democracy places the U.S. within a broader global trend—a 15-year democratic recession that some have called the “Third Wave of Autocratization.” This means that there many contemporary cases with lessons to learn. And of course we have hundreds of cases from history that provide valuable lessons—including emancipatory campaigns in the US—about how to defeat both backsliding and even full authoritarianism through civil resistance. The best study on the subject in my opinion suggests that in the long term, institutions really can’t save us; that civil society and mass mobilization are a more potent check on a backsliding democracy in the long-term than relying on institutional checks and balances alone.

Last night I was re-reading a paper that Zoe Marks and I wrote in 2022 about how U.S. civil society might prepare for a moment like this, based on our analysis of those lessons. To defend democratic principles and improve upon US democracy, we concluded that we would ultimately need to build what the successful democracy movements of the 20th century were able to create: a united democratic alliance. This would involve a coalition of pro-democratic grassroots and grasstops [high profile] civic groups, political leaders, business leaders, faith leaders, unions and workers’ groups, and the like, working in concert at the local, state, and national levels to build and implement a strategy for expanding democracy in the US. An effective strategy would combine legal, institutional, and civil resistance methods to advance the pro-democratic agenda. It would spell out a positive and optimistic vision for the country, rather than a defensive strategy. It would be disciplined and resilient to inevitable setbacks, and it would mobilize mass protests or strikes as it saw opportunities to turn its power into tangible leverage.

There are many concrete capacities that might go along with this – from a more robust and sophisticated way of communicating information to popular education to gathering and vetting information to inform and update strategies to providing mutual aid to creating alternative institutions that build parallel power. Successful democracy movements of the past have found ways to build these capacities under authoritarianism, even if they weren’t engaged in constant street protests over the life of their movement (they mostly weren’t). There are some wonderful formations already engaging in such work, but I hesitate to name them here so as not to make them targets....

Rebecca: What are some of the tactics, strategies, examples we can look to? People are eager to figure out what to do, what power we have, how to exercise it, and while there are a million to-do lists and calls to action and ideas out there, I think people would really benefit from tested methods and concrete examples.

Erica: There are so many cases. Off the top of my head, in Serbia in 2000, Slobodan Milosevic called for a snap election to shore up his power in the midst of an economic crisis after years of war, as well as growing protest and discontent. Civil society groups seized the opportunity and convinced dozens of opposition parties to unite behind a single unity candidate to challenge Milosevic. The opposition candidate won in the first round, but Milosevic fraudulently claimed victory. Anticipating this outcome, the movement had organized parallel vote counting and, through some independent media outlets they have cultivated, communicated the accurate outcome nationwide. They called for mass demonstrations in Belgrade, drawing in people from all over the country and all walks of life. Loyalty among Milosevic’s security forces collapsed under this political pressure, and he resigned.

In South Africa in the 1980s, there was no possibility of ending the apartheid regime through elections, as black South Africans could not vote. Despite the African National Congress (ANC) having been banned, over many years a coalition of trade and labor unions, journalists, civic groups, faith groups, and local community networks built a broad and powerful coalition that challenged the white supremacist apartheid regime. The coalition built the capacity for mass mobilization, mass noncooperation, and mutual aid—even under sustained martial law, repeated roundups, and lethal repression by the apartheid regime. They adopted a strategy of building economic pressure on status quo elites and to make the necessity of democratic reform inescapable. Toward the end of the campaign to end apartheid, black townships demonstrated their economic power by engaging in general strikes and well as consumer boycotts against white-owned businesses. Combined with international sanctions and multinational corporations divesting from their holdings in the country, the business sector challenged the pro-apartheid National Party to reform itself and come to terms with the opposition. A reformer, F. W. deKlerk was elected to lead the National Party, the ANC was unbanned, Nelson Mandela was released from prison, and an interim constitution was negotiated, leading to a full democratic transition. (There is a reason why Elon Musk is trying to reshape the narrative about South Africa today, erasing the country’s astonishing path out of white supremacist authoritarianism).

And, of course, there are examples from our own country, where over the past 125 years, every major expansion of the franchise, and every major achievement in civil rights and/or social, economic, or environmental justice, was fought for and won by some form of a people-power movement—whether that was the labor movement, the Suffragists, the Civil Rights Movement, the farm workers’ movement, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP), the movement for the rights of people with disabilities, the environmental movement, or even the effort in 2020 to Protect the Results after Trump fraudulently claimed an election victory.

There are countless tactics and strategies available, though there is no cookie-cutter recipe to apply in any one case. But I think one main lesson that emerges is that, in order to have the capacity to develop winning strategies and tactics, a broad-based coalition is really vital. Focusing on building that capacity, those connections, and that coalition around shared values, from the neighborhood to the national level, would be very useful.

Folks can gain knowledge, hope, and inspiration from lots of prior democracy and/or anti-colonial movements. A good place to start is the documentary series A Force More Powerful, with short and informative segments on the Salt March in India, the Nashville desegregation campaign in the late 1950s, the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa, Danish resistance against Nazi occupation, the Solidarity movement in Poland, and the anti-Pinochet movement in Chile. Many of these are relevant to our current moment, and I’d recommend watching them again (here and here) even if folks have seen them before. Another documentary highlights the role of the youth movement Otpor in Serbia’s Bulldozer Revolution. For many years, George Lakey has been co-creating with students a database of nonviolent campaigns of many different types, and there are detailed descriptions of the methods used. And, of course, there are many resources available at the International Center on Nonviolent Conflict, the Albert Einstein Institution, Training for Change, Beautiful Trouble, and beyond.

In a conversation I had with the late Rev. Dr. James Lawson about ten years ago, he told me that when he was planning and preparing for the campaign to desegregate Nashville, he had very little material to work with: “only Gandhi’s autobiography and the Bible.” He said something like, “You all have books on strategy, training manuals, institutes that specialize in teaching and study, and hundreds of historical examples to draw from. You are lucky!” People have agency, no matter what happens. And knowledge is power.

A footnote of sorts: Erica's 2014 Ted Talk on what became known as the 3.5% principle– the percent of a population it takes to succeed at nonviolent regime change--is still worth watching at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YJSehRlU34w&t=2s. The figure of 3.5% comes from their earlier research on nonviolent social change, but they caution me that people have taken the (now much cited) 3.5% figure as a talismanic fact rather than an average. Here's some key points from their 2020 "cautionary updates" study: "The 3.5% figure is a descriptive statistic based on a sample of historical movements. It is not necessarily a prescriptive one, and no one can see the future. The 3.5% participation metric may be useful as a rule of thumb in most cases; however, other factors—momentum,organization, strategic leadership, and sustainability—are likely as important as large-scale participation in achieving movement success and are often precursors to achieving 3.5% participation rule, and that the rule is a tendency, rather than a law. Large peak participation size is associated with movement success. However, most mass nonviolent movements that have succeeded have done so even without achieving 3.5% popular participation." They further add that these movements in the study had the goal of "overthrowing a government or achieving territorial independence. They were not reformist in nature, and they had discrete political outcomes they were trying to achieve that culminated in the peak mobilization that I counted. Because of this, we cannot necessarily extrapolate these findings to other kinds of reform or resistance movements that don’t have the same kinds of goals."

I asked Erica one more question:

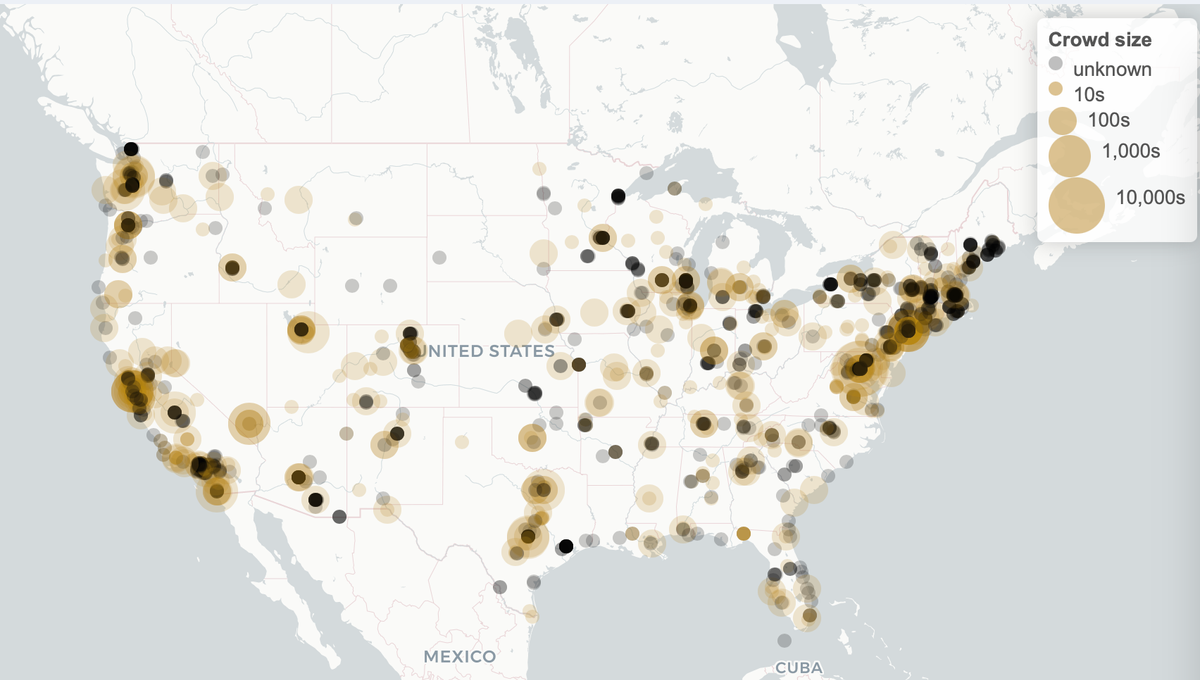

Rebecca: And finally, the Crowd Counting Consortium did extraordinary work, notably by quantifying the huge size and geographic distribution of anti-Trump marches known as the Women’s March of January 21, 2017. Will it be back in action for anti-Trump/anti-Musk protests at present?

Erica: We have been continually producing data on protest, counter-protest, and police response since the first Women’s March in 2017. We will continue to do so as long as we’re able. See here and here.